The couple caught on a 'kiss cam' at a Coldplay concert sparked a discussion about public shaming online. Photo: Supplied

Explainer: Privacy. We all want it, but it's not always easy to get.

These days, the internet has made everyone a publisher and it's very easy to suddenly find yourself 'main character of the day' on social media.

There is no easy fix for viral infamy, but there are some tools that can help.

Here are a few ideas on what you can do about public shaming and some of your privacy rights online.

What are the rules about being filmed in public?

People often think they need to be asked for permission before someone takes their photo in public, but that's not actually the case.

Taking photos of people in public places without their consent is generally legal, NZ Police said, but there are exceptions.

You can't take photos of people in a place where they could expect privacy, such as a public changing area or toilet.

The police said you should not take photos of people if "they are in a place where they would expect reasonable privacy, and publication would be highly offensive to an objective and reasonable person".

Online safety organisation Netsafe's deputy chief executive Andrea Leask said places like parks and beaches were public spaces.

"Under New Zealand law, individuals are generally free to take photos or video people in public spaces - like streets, parks, beaches, malls and concerts - and publish this content without consent, as there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in such places.

"It is also illegal to intentionally film another person's intimate body parts without their knowledge or consent, even in public, when they have a reasonable expectation of privacy," she said. "An example of this is upskirting - photos or filming under a person's skirt or dress."

The intention of the photograph can matter too.

"An agency publishing a photograph of a person for the purpose of causing them harm or embarrassment is likely to breach the Privacy Act," a spokesperson for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner said.

Photo: Supplied

So what's our right to privacy?

That act - the New Zealand Privacy Act 2020 - lays out 13 privacy principles that govern how organisations and businesses can collect, store and share personal information. That may cover things such as your photograph being used in an advertisement, or your personal information being published online.

But in practice, on social media, privacy can be a bit of a moving target.

The 'Coldplay kiss cam' scandal in July reinforced the idea that privacy these days is fragile when everyone has a phone in their pocket.

That incident saw an IT company executive caught in a public clinch with an employee during a Coldplay concert, resulting in them both leaving their jobs after the band's frontman Chris Martin quipped, "Either they're having an affair or they're just very shy."

Kathryn Dalziel is a privacy lawyer based in Christchurch. She said the Coldplay situation showed the pitfalls of filming in public spaces.

"If they weren't having an affair that could amount to a defamatory statement," Dalziel said. "The camera should have gone off them the minute they didn't want to be filmed."

The Privacy Commissioner's office said there are options if you feel targeted by a post online.

"People can ask the social media platform to remove the content. They should also think about getting legal advice, to see what options are available. Depending on the case, there could be defamation, harassment, a civil claim or other legal avenues."

You can also file a complaint with the Privacy Commissioner. If they find a breach has occurred they can try to settle it or carry out a formal investigation.

They can't issue fines or force people to accept their findings, but they do try to help both groups come to a decision about how to resolve the issue.

However, the Privacy Act does not generally apply to individuals - unless the information involved is "highly offensive".

What's highly offensive, then?

The test to decide if something is highly offensive is "whether an ordinary reasonable person would think that what has happened is a breach of an individual's reasonable expectations of privacy", the Privacy Commissioner's office said.

"A social media post could be highly offensive if it encourages people to harass or hurt someone, or if the person it is about is particularly vulnerable. The nature of the content posted may also mean other legal alternatives or criminal action is possible.

"For example, sharing an intimate recording online could potentially raise other offences under the Crimes Act, s 216J. There could also be issues under the Harmful Digital Communications Act or the Films Videos and Publications Classification Act."

Photo: Pixabay

What if someone goes after me with false comments on social media?

If you're being harassed, Netsafe offers a wide variety of tools to help the public.

"Netsafe is excellent," Dalziel said. "They really are quite good about process and things like that."

- How to contact Netsafe for support

- How to make a complaint to the privacy commissioner

- About the Harmful Digital Communications Act

- Other ways to complain about a privacy breach

I really don't like what's been said about me. Can I sue for defamation?

Defamation law aims to protect people from false publicly published statements, although it's not always an easy option. The burden of proof to establish those claims is on the plaintiff.

"I get inquiries every so often from regular people who have been defamed on social media," said Nathan Tetzlaff, a senior associate at Auckland law firm Smith and Partners.

"On initial review, I'll often find that there was a defamatory statement made, however the costs, stress and time involved in legal proceedings tend to put people off."

Defences against defamation can be that the statement was truth, honest opinion or given with the complainant's permission.

Filing a defamation claim, especially if you are a prominent or public figure, could bring more unwelcome attention than the original defamatory statements did, Tetzlaff said.

But there have been successful recent defamation cases involving ordinary people in New Zealand, he said, such as a post on a sports association's social media pages accusing people of misuse of funds, or a business dispute resulting in smear campaigns online.

"I would say defamation is for politicians and rich people and celebrities," Dalziel said. "In New Zealand, cases of defamation involving politicians and media people have succeeded."

There have been calls to reform the Defamation Act 1992. Tetzlaff said that could include adding a threshold so that the plaintiff needs to be able to prove some minimum level of harm financially or to their reputation and expanding remedies to include a court-ordered apology.

"I think that setting a higher threshold would be significant," he said.

"As much as ordinary people don't tend to go to court over defamation, all it takes is one ill-considered post and a person has technically defamed someone, and may be subject to legal threats and the risk of actually being taken to court if the victim has the means and willingness to do so.

"This can give people of means an avenue to bully and silence critics which might not be in the interests of justice. There's a balance that needs to be found."

Photo: vectorstock

Are 'name and shame' posts on social media legal?

You probably won't go a day on social media without finding a post with a picture of someone being accused of theft, road rage or just general unsociable behaviour. It only takes a few clicks on Facebook to find 'Name and Shame' pages. But are these posts legal?

Under the Harmful Digital Communications Act, online content or messages that intentionally cause severe emotional distress can be illegal.

Police said they don't endorse such behaviour.

"Police would recommend that instead of posting images or details of an alleged offender online, you should report the matter to police to investigate," a police spokesperson said.

"While it is not illegal to post these details online, people who do are risking opening themselves up to other legal ramifications such as defamation proceedings."

Leask of Netsafe said the pages may be legal, but posts can sometimes break the rules.

"These types of pages are tricky because they can deal with a myriad of different rules. In general, if the information being shared on these pages is public record, for example, most convictions, then it is legal to share.

"However, there are limitations around harassment, defamation or provisions for name suppression. Another factor is the Clean Slate Act, which legally protects certain old convictions from being disclosed."

Tetzlaff said such pages can easily cross the line.

"'Name and shame' pages can certainly give rise to defamation, assuming that the defences of truth or honest opinion don't apply. There is no protection or privilege given to allegations made on these sorts of pages."

One post RNZ saw discussed an alleged scammer and the poster said they knew the person's address "in case anyone wants to waste a few eggs".

"People doxxing and saying where you live in my view is heading to a measure of criminal interest," Dalziel said. "That can amount to harassment."

Dalziel also said such posts can frequently breach terms and conditions for sites such as Reddit and Facebook.

Netsafe also offers advice for those who have been doxxed, and potential remedies.

What happens if my boss finds out?

There are many cases of a social media post coming back to bite people on the job.

Employment New Zealand notes that "activity on social media may be a cause for disciplinary action, including dismissal if it is serious or repeated".

It recommends that employers set out social media policies clearly stating what is unacceptable behaviour, such as ones critical of the workplace, divulging commercially sensitive information or activity that "is inconsistent with the values of the company".

"In fairness to your employer, you want to have a talk with them as quickly as possible" if you find yourself the victim of an online scandal, Dalziel said.

But while the Coldplay scandal couple did leave their jobs, it would be a lot more difficult for an employer to sack someone over something like that, Dalziel said.

"I find it outrageous for any employer, unless they were a political organisation, to say that it affects their business if (people) were having a relationship in a workplace," she said. "Our morality as a culture is that it's nobody's business."

Dalziel cited an infamous New Zealand example from 2015, where a married office worker and a junior employee were filmed having sex clearly visible through their office windows by pub patrons across the road.

"Their pictures ended up all over social media over the weekend and by the following week they were called into being investigated by their employer and both of them left their employment.

"The same issues came up at that time and the advice generally was that this was in public, so they didn't have a reasonable expectation of privacy and there was little remedy in law."

It can be difficult to get social media posts removed. Photo: AFP

Can I get posts about me removed from the internet?

It can be difficult, but it's possible depending on the situation.

There are companies that will help 'scrub' your posts online - although given the slippery nature of the internet it's never foolproof - as well as a variety of 'reputation management' companies.

"There are companies that are set up to clean the internet as far as they can," Dalziel said. "They can reduce the amount of reports so that (an incident is) not coming up every time your name is on Google. It will for a wee while, but it will reduce over time."

Is this just life in the digital age now?

"People sometimes forget that posting online can have real world consequences," the Privacy Commissioner's office said. "Posting another person's image can impact that person."

Dalziel encouraged people to think twice before joining the latest pile-ons.

"We are sitting in an environment where we are learning a new morality based on the internet. I think there's a duty on people to go back to good values.

"Ask yourself why are you wading in, why are you joining in, why is it you think you are the font of all morality," she suggested. "Are you without sin and are you casting a stone, why are you doing that?"

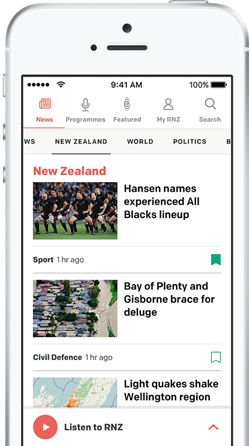

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.