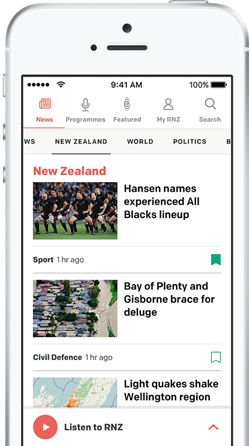

Di Maxwell and Jack Poutsma outside the former BNZ building they restored and earthquake-proofed Photo: Peter de Graaf

Earthquake-proofing heritage properties just got more doable for their owners, and the result could be a drop in the numbers of vacant and abandoned buildings.

They dot the main streets of small towns. Masonry buildings built after the turn of the last century, vacant or abandoned, the cost of getting them up to code just too much for the owners to shoulder. Often they sit there until a fire destroys them.

A new change in earthquake-proofing regulations could go a long way towards rescuing them.

The move to decouple retrofits from other Building Act requirements, which often adds unbearable costs to the job, could prompt building owners to finally embark on the work, according to Associate Professor Olga Filippova, from Auckland University's Department of Property.

She was involved in research for the MBIE report that formed part of the recent government review, providing perspectives of seismic risk mitigation in earthquake zones overseas, including Japan and California.

"The truth is it's difficult, and no one has answered it," she said.

Japan came closest to mitigating the risks, prioritising public safety at the government level and giving grants to property owners to secure their buildings.

She said while the messaging in last Monday's announcement by Building Minister Chris Penk was more about saving money (an estimated $8.2 billion) than saving lives, the changes move New Zealand closer to international best practices by focusing on the worst risks, simplifying retrofit requirements, and causing less disruption.

One of the issues stopping owners from upgrading their earthquake ratings in the past has been requirements that if they embarked upon the work, they also had to get the buildings up to new fire and disabled access codes - work that often cost far more than the earthquake strengthening.

Things can change

Filippova said regulations introduced after the Christchurch earthquakes were a knee-jerk reaction to the horror of building collapses, but because of the scale of them, "we had to act".

"Clearly things weren't working. I think we went too broad right at the beginning," she said.

"We just put a blanket mandate across the country, capturing many different building types without really looking at what's been happening overseas.

"In California for example legislators went first after the most vulnerable structures, which were unreinforced masonry buildings, the sort that are prevalent in small towns here.

"Often they are two to three storeys and have a parapet on top - the sort of fixture that would fall to the footpath in a big shake."

Filippova said in many cases such buildings here were only occupied on the ground floor because of the lack of earthquake proofing.

"I see a lot of public good in those older buildings, which I think there is absolutely a strong case to providing financial incentives to building owners to help protect those buildings."

One of the other changes lets Auckland, Northland and the Chatham Islands off the hook for seismic retrofits, because they were in low risk zones.

But low risk is not no-risk, Filippova said, and labelling it as such was a mistake.

She said it sent "a signal that the risk almost doesn't exist. Whereas the risk is always there, and really it's just a lower risk, rather than just low risk. And so of course now we have this perception that, well the risk is low so we don't need to do anything."

She pointed out that before the Christchurch earthquakes we didn't know there were faults running under the city.

"Things can change."

Di Maxwell and Jack Poutsma in their beautifully restored heritage building in Kaikohe Photo: Peter de Graaf

Also on The Detail, we talk to Di Maxwell, who with her husband rescued Kaikohe's only heritage-listed building when the BNZ bank abandoned it.

It was virtually worthless after an earthquake report put the cost of a retrofit at $400,000.

The couple ended up spending nearly $2 million restoring it, of which $600,000 was for earthquake strengthening.

If they had embarked on that work now it would be a completely different story.

Maxwell recounted the work they had to do, their struggles and frustrations with the regulations and what she described as over-engineering by professionals terrified of being held accountable if there was a shake and someone was killed.

The building was now well over-capitalised, but "it's going to be safe for another hundred years, at least," she said.

"It will long outlast us, that's for sure. And not everything's about money, is it."

Check out how to listen to and follow The Detail here.

You can also stay up-to-date by liking us on Facebook